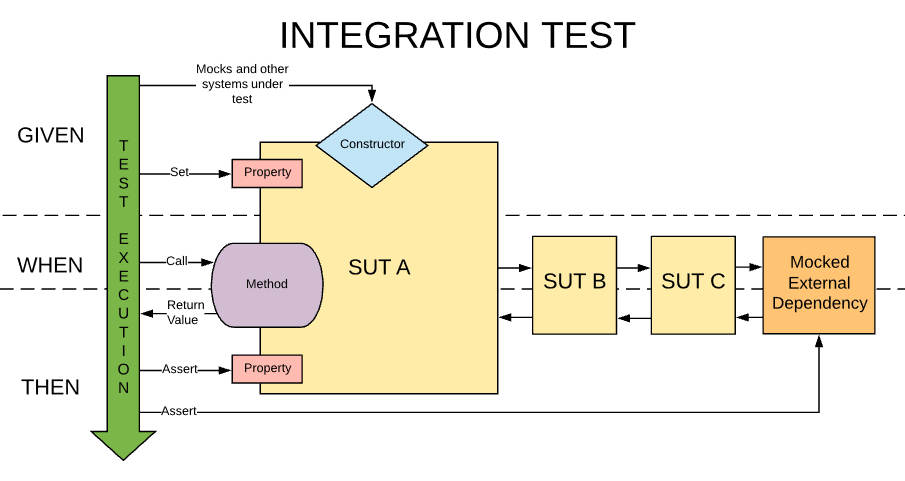

Integration Tests, in contrast to Unit Tests, test the behavior of more than one unit of our code when working together. This may be as simple as testing two classes interacting together, or we might bootstrap most of our application to be tested. In fact, some of the most useful types of Integration Tests are designed to test as much of our codebase as possible while still isolating it from external dependencies, such as third party APIs, the filesystem, or databases.

Below is an example Integration Test:

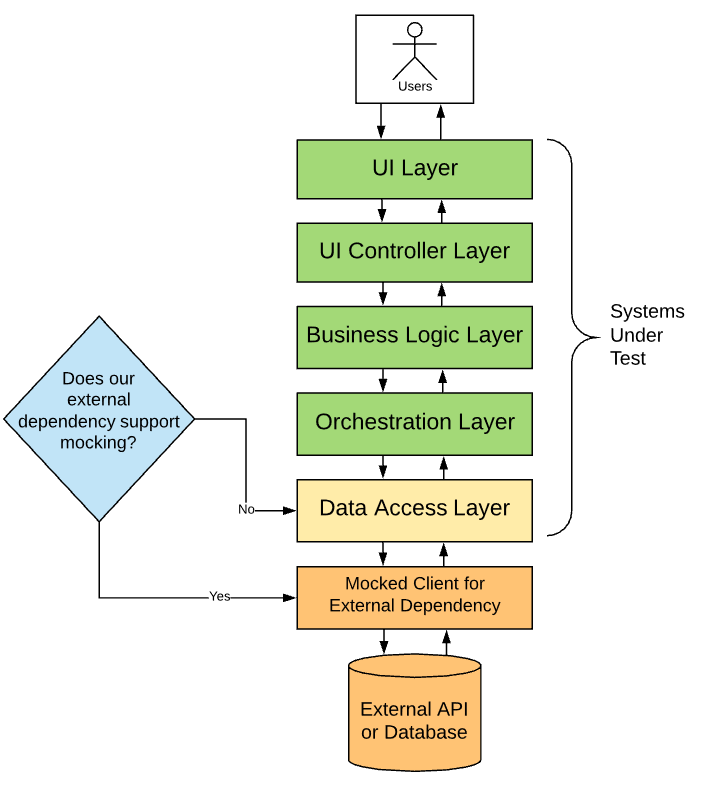

A useful way of conceptualizing a large-scale Integration Test is by considering a single application with a layered architecture, with each layer in the stack having its own type of responsibility:

In the above example, we will wire up the real implementation of classes in our stack from the top of the stack, all the way down as close to the bottom as we can get while still abstracting away external dependencies. Ideally we will have a clean interface to consume which handles communication with our external dependencies, such as a class in a third party library. But we are not always so lucky, and in this case we can use mocked versions of our interfaces that represent the Data Access Layer, which is responsible for reading and writing data to our external dependencies.

Purpose of Integration Tests

Due to their larger scope, Integration Tests are more complex to set up than Unit Tests, yet they test things which cannot be tested by Unit Tests. Unit Tests assert the correct behavior of a single unit of code in isolation, but Integration Tests help us ensure that they behave correctly when working together. As an example, imagine that we have two classes, UriHelper and FooBar which interact, and a test asserting that when FooBar‘s UriHasHostName method is passed a null URI, it will return false.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

public class FooBar

{

private UriHelper _myDependency;

public FooBar(UriHelper myDependency)

{

_myDependency = myDependency;

}

public bool UriHasHostName(string uri, string hostName)

{

return _myDependency.GetHostName(uri).Contains(hostName);

}

}

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

public class UriHelper

{

public string GetHostName(string input)

{

Uri uri;

var succeeded = Uri.TryCreate(input, UriKind.Absolute, out uri);

if (succeeded)

{

return uri.Host;

}

else

{

return null;

}

}

}

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

[Fact]

public void UriHasHostName_PassedInvalidUri_ReturnsFalse()

{

var sut = new FooBar(new UriHelper());

var result = sut.UriHasHostName("blah", "google.com");

Assert.False(result);

}

Did you spot the bug?

Instead of passing, our test throws an exception on line 5. While the behavior of both classes might be considered correct in isolation, the way FooBar consumes the return value from UriHelper‘s GetHostName method is invalid and leads to a NullReferenceException at runtime. Because GetHostName returns null when it is provided an invalid URI, and FooBar does not properly check for null responses, these two classes (despite their implementations being potentially valid in isolation) cause a runtime failure.

Bugs like this, where the interactions between two classes in our codebase are built upon faulty assumptions, are the sorts of bugs that we can identify and protect from using Integration tests.

Thinking Bigger

The previous test was useful to illustrate a faulty interaction between two classes, but what if we want to test our entire codebase? Writing some happy path tests that assert that our codebase can function correctly in some common use-cases can be an excellent guard against a wide variety of regression bugs in our codebase.

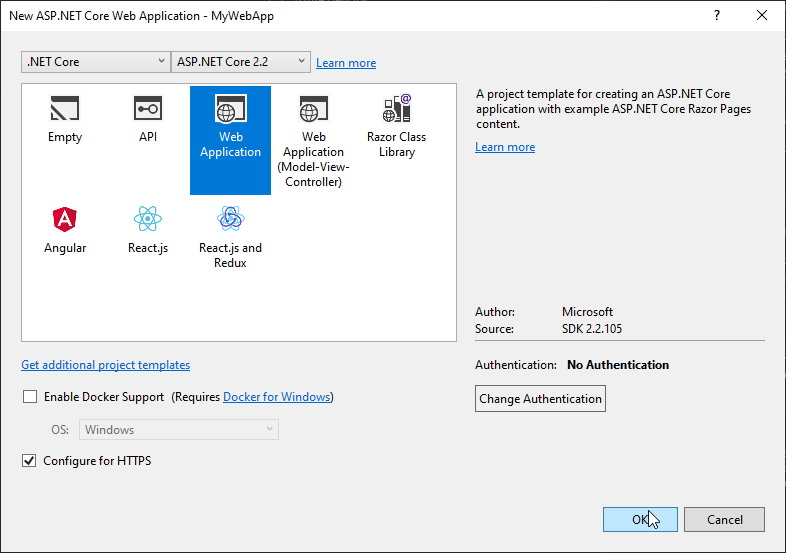

For this example, let’s create a new ASP.NET Core web application in Visual Studio, then add an XUnit test project to the solution:

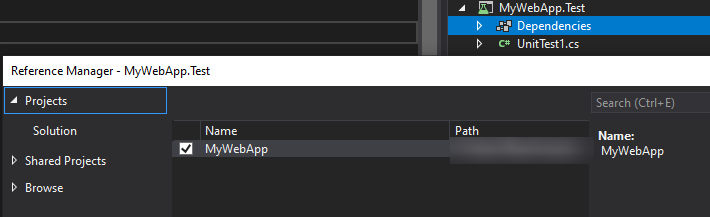

Next, let’s add a reference from our XUnit project to our webapp:

Next, let’s add a reference to the Microsoft.AspNetCore.Mvc.Testing NuGet package in our Test project:

This package contains useful tools for designing Integration tests like the one in this example. In particular, it contains the WebApplicationFactory class which can be used to bootstrap an in-memory instance of our web application, along with a client that can be used to route HTTP requests to it over the loopback. The WebApplicationFactory constructor accepts a generic type argument, which is the type of the Startup class which will be used to bootstrap our web application. A trivial test using this class looks as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

[Fact]

public async Task GetAsync_Index_ReturnsSuccess()

{

var factory = new WebApplicationFactory<Startup>();

var sut = factory.CreateClient();

var response = await sut.GetAsync("/Index");

response.EnsureSuccessStatusCode();

}

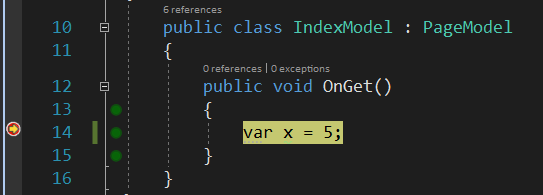

Once we have written this test, we can then test that it works by setting breakpoints in either the Startup class or in the codebehind for the Index path (Index.cshtml.cs) Then we can run the test in our debugger and see that our breakpoints are hit:

Because our current implementation has no external dependencies, this can already be considered an Integration Test. However as we expand our application’s logic, we will likely take on external dependencies. How do we mock them?

The most straightforward way is to provide a second test double implementation of our Startup class which provides mocked versions of our external dependencies to the DI container in its ConfigureServices method, while using the live implementation of all of our classes which do not directly interact with external dependencies:

1

var factory = new WebApplicationFactory<IntegrationTestStartup>();

If you are working on a .NET codebase and are interested in more details about integration testing, Microsoft has some good documentation on the topic.

Why We Mock Our Dependencies

While it is possible to design large-scale tests such as these without mocking our external dependencies which makes them more realistic, those would be considered System Tests and have two major drawbacks which Integration Tests do not:

- They are generally much slower due to depending on slow operations like network I/O, and hard disk or database access.

- They can fail due to problems outside of our codebase, which makes them unsuitable for use as quality gates during our build process – we don’t want our build to fail just because a third party API is having a bad day!

Both Integration and System Tests have their place, but one of the major strengths of Integration Tests is that they are the most complete way to exercise our codebase while still having their result be solely dependent upon the contents of our codebase.