When planning out our tests, it is important to consider whether they are valuable. While it is easy to see the value of a test - it tells us if something in our software is broken. Yet it is also important to consider the costs of our tests to ensure that they do not outweigh the benefits.

The beauty of test automation is that once a test has been written, we can reap the rewards each time it is run. Therefore all of the benefits of the test are recurring. But the costs of tests are are divided between one-time costs, and recurring costs. First, let us consider the different benefits we might get from a test.

Recurring Benefits of a Test

- Time saved testing features manually

- Prevention of severe or likely defects

- Well-designed automatic tests perform the test steps more reliably than human testers, reducing the odds of a false negative

- Automatic notifications of failures before code is merged to the mainline, potentially impacting other team members

- Earlier detection of errors, which allows them to be fixed without introducing a context switch

- Testable code and UIs tend to be simpler and thus easier to use and maintain

- When a test fails, the test itself is a complete set of reproduction steps for the failure, which simplifies the documentation of defects

- Tests represent executable documentation about our software’s functionality. Unlike traditional documentation, we can easily verify that the tests accurately reflect the software at any time by executing them

As you can see, the benefits of automated tests can be myriad. Yet there are also costs to consider:

One-Time Costs of a Test

- Time spent writing the test

- Time spent modifying the UI or code to make it testable

- Cost of any software licenses required to design or execute the tests

Furthermore, tests also have recurring costs to consider:

Recurring Costs of a Test

- Maintenance of tests

- Maintenance of test data

- Time wasted troubleshooting false positives in unreliable tests

- Server time/CPU costs of executing the test

- Delay cost of waiting for tests to complete before deploying code, merging a PR, starting another test suite, or promoting to a test environment

An important thing to consider when designing tests is whether the costs of a test might outweigh its benefits. A poorly designed test that fails due to timing, data issues, or dependency issues can actually sap more time from your testers or developers than it saves by preventing issues, resulting in a test that actually slows the forward progress of your software rather than enabling it.

Just as businesses conduct cost-benefit analyses when considering business strategies, we should also weigh the cost and benefit of our tests to ensure that our test portfolio offers us the greatest value possible. Note that while it is possible to document the benefits and costs of a test explicitly, this will more commonly be a matter a professional judgement on the part of the developers and testers building the test suite. It is important to identify techniques and principles which allow us to design our tests in ways that maximize the benefits of tests, while minimizing their costs.

Maximizing the Benefits

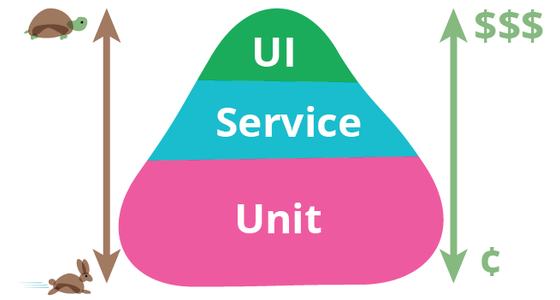

When designing our tests, two basic principles can help us ensure that they are as valuable as possible. First, the Test Pyramid:

As we design our tests, we should bear in mind that as the scope of our tests increases and includes more of our code, and even other systems, the time and cost of maintaining and executing the test also increases. Thus we should aim to have a small number of UI tests which test the most important features of our products, while having a very large suite of Unit Tests which may each take less than a millisecond to execute while testing only a few lines of code. In other words, we should ensure that the value of what is being tested is high when the cost of the test is also high.

The second principle to bear in mind as we design our test portfolio, is the “shift left” mindset. In other words, when devising a test plan for our software, we should design tests as early in the lifecycle of a feature as possible. Acceptance criteria identified by testers during dialogue with a stakeholder might form the basis of future unit, integration, or UI tests.

The shift left mindset also applies to test execution as well as design - in other words, if we can adequately test some aspect of our software with a Unit Test, which is often executed on a developer’s machine even before code containing a defect is committed, we should do so. Conversely, since UI tests are our most expensive form of tests, they should be used as a last resort on features that are UI specific or depend on interaction between many codebases and cannot be reasonably tested in other ways.

Minimizing the Costs

However great the potential benefits of a test, if the cost of maintaining and running it is too great, it can still be a detriment. Below we will discuss some techniques for mitigating the cost of our tests.

Test Data Management

A common source of unreliability in tests is improper management of test data. If a test can only pass when certain data in a database or elsewhere is in a certain configuration, this introduces a single point of failure in our tests.

A useful strategy for managing test data is simply to create it all from scratch at the beginning of the execution of a test or test suite. Rather than logging in as an existing user, for example, we might create a new user in exactly the configuration needed to perform our tests. Then when our tests have finished execution, they should also clean up this temporary test data by deleting the user (whether they pass or fail!)

However this is not always possible - some resources may take minutes or hours to create from scratch, in which case it may be prohibitively expensive in terms of test execution time to create all of our test data on each execution. In this case, existing test data may need to be used, and we can use other techniques to increase its reliability.

One important technique is good naming conventions - persistent automated test data should be named such that its purpose is clear so that it is not accidentally modified during the course of manual testing. As an example, we might use automated-test-user-12-25-2019@example.test as a test user name. A developer or tester performing manual testing who happens across this user will readily realize that modifying the user could impact the automated tests.

Another way of improving reliability of tests that rely on shared data is to design automated diagnostics of test data - possibly within the test suite itself. For example: a test that attempts to modify a certain user setting might first check that the user exists and is in a valid state. If the user has been left in a bad state or deleted somehow, this step should generate appropriate logs so that it is clear which test data needs to be reconstructed.

Timing Issues

Another common source of unreliability in tests is timing issues, such as the dreaded thread sleep:

1

Thread.Sleep(3000);

In scenarios where your test needs to wait before taking the next action, it is always better to have the test wait for something - such as a UI element becoming visible, a page to load, or for a database record to be updated. Many test frameworks have built-in tools to do this, but if yours does not, you can design the test to check for the completion of whatever you’re waiting for in a loop until the operation you’re waiting on is done (just be sure to include a timeout so you don’t accidentally wait forever if something goes wrong!)

Updating the Code to be Testable

While the bulk of the work in designing Test Automation centers in the creation and maintenance of test code and scripts, it is important to view the design of the software under test as being part of the testing process as well. Applying clean coding techniques such as SOLID makes it easier to write and maintain unit/integration tests. Likewise it is important to design a UI which is simple to use (and therefore simple to test.) Furthermore, your UI should include useful metadata markers on items of interest (example: “id” tags on an HTML element) which allows your code to find UI elements without resorting to more brittle methods of finding the elements such as complex CSS/Xpath queries or X/Y screen coordinates.